Achieving a Work/Life Balance: True confessions by Todd Ellison, 2020

Abstract: We all need to rest and to have a full, meaningful life. This article offers thoughts, philosophies, strategies and examples (good and bad) that will relate to individuals who do archival and records management work within government agencies. A key thought, especially for nowadays, is that we can ditch the illusion that we can maintain a regular daily balance—but we sure can use tips for engineering a work/life balance that will last for the rest of our lives

|

Five parts of this article:

One: Overview and COVID-19-era thoughts

Two: Practical strategies

Three: Life has its seasons

Four: Practical tweaks we can make

Five: Two physical analogies in conclusion

One: Overview and COVID-19-era thoughts

Two: Practical strategies

Three: Life has its seasons

Four: Practical tweaks we can make

Five: Two physical analogies in conclusion

Part One: Overview and thoughts particular to the coronavirus era

Each and every one of us was, in effect, writing our own versions of this article for most of the year 2020. How is it possible to achieve a new and improved balance between the demands of work and the broader realm of all of life?

I started preparing this topic midway through 2019 – Before Coronavirus. From here on, it seems likely that we all will be viewing every aspect of the recent past in terms of whether it was before or after the perplexing and convulsive worldwide events that started to shake our world by early 2020. This choice of topic, which the NAGARA committee selected for an October 1st webinar presentation prior to all that, has seemed more apropos with every passing day.

Never in our lifetimes have we seen the reset button hit in the way it was in 2020. This forced us to stop and readjust our lives. We do not work the same way, our daily routines have been revolutionized, and our sense of what really matters has been sharpened. Never in the history of the world have so many millions of people been compelled to not work, and, in the case of many individuals in some countries including ours, been paid to not work.

One of the positive results of the Covid-19 situation has been a simplifying and decluttering of some aspects of life. We are staying home a lot more, traveling a lot less, and fewer of us have been employed full-time. Perhaps (like me in the middle of this year), you received orders to not work quite so much.

The boundaries of our seashore have been more firmly established than they were the year before. Some protective breakwaters have been established, and more are under construction. Also, we have had to eliminate a lot of things that are not now considered essential. And perhaps there has been some excess that needed to be trimmed away, at any rate.

Some of the aspects of this change have had their benefits, but a lot of it has been difficult—more so for some than for others. The suffering has been real, and the impacts have been bewildering and longstanding. All of this ties in to our topic: how to achieve a work/life balance.

The following four points are the essence of what we will consider in this regard:

• 1. Each of us has a deep need for a full life, rest, and long-term meaning.

• 2. Most of us, much of the time, we cannot maintain a daily work/life balance.

• 3. We can engineer a balance that should last for all our days.

• 4. We can adopt practical strategies that apply to archival/records management work within government agencies.

If there is only one point you take from this article, this may be it: achieving this balance starts with my inner self-talk as to who I am. At the core, we are not records managers or archivists. We are individuals who use part of our talents, aptitudes and motivations to make records available to all who need them, who have the right to see them, for as long as anyone may need them.

We can tend to become ensnared by the belief that we are what we do. “What do you do?” tends to be the first question many of us ask when meeting another adult. By that, we mean, “What is your occupation?” That is not always the most helpful question, because the answer may not give us the essence of who this person is. In his book on An Unhurried Life, Alan Fadling wrote that actually, “what we do is an expression of who we are; what we do does not establish who we are.”[1]

Alan Fadling added that people who say, “I’m going to lose myself in my work” are saying more than they realize. Do we really want all the consequences in the following list?

• Driven-ness to achieve

• Narrow time for escape

• Dogged absorption in detail

• Hyper-responsiveness

• Dashed and dented relationships

• Impaired physical health

Would we prefer to fulfil this list, instead?

• Work that uses our talents

• Health-friendly work environment

• Balance of urgent and important

• SMART prioritization of tasks

• Movement built into the workday

• Scheduled time away from work

A healthy person needs hearty work and regenerating refreshment.

While I was doing the research for this topic, a university professor in his early 50s took his own life. He was a gifted educator but had made a number of unpopular statements on social media and had recently settled with the university for early retirement. The half a million dollar settlement apparently did not mean much to him. His identity, it seems, was so tied to being that professor, and his dismay at how unpopular his views had made him after 20 years in that role was so great, that he apparently thought he could not carry on. His is perhaps one of the most extreme examples of the effects of a work/life wobble, stemming from a lopsided view of who we are. It can be instructive to us.

A healthy person needs the balance of hearty work and regenerating refreshment. This is not at all the same as driven achievement and narrow escape time.{2} We are fortunate, I think, in that most of us like the work we do, and find it rewarding. U.S. Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska wrote a book last year, Them: Why we hate each other and how to heal, in which he cites research documenting that to be happy, people need to be doing work that matters. In particular, we need to be doing something that benefits others, not just ourselves as the worker. He noted that this is one of just four things humans need, for being happy.[3] Isn’t that why we often go the extra mile to assist a researcher, to provide information that will just “make the day” of someone else?

Thus, our work forms an important part of our personal identity, but we are much more than what we do. The recognition that each of us has a uniquely designed all-encompassing personal identity is the key to achieving a work/life balance.

Paul Tournier, a Swiss physician whose career was focused on helping individuals via a wholistic approach, wrote a book in 1957 called The Meaning of Persons. He wrote that “We are the slaves of the personage which we have invented for ourselves or which has been imposed on us by others.”[4] Our schooling, our credentialing, and the workplace behaviors that will earn us professional success and acceptance by our colleagues have been shaping the roles we act. They have in fact made us, in part, who we are today.

As Dr. Tournier saw so many decades ago, our individual personhood has been eclipsed by the persona we must present in our professional work. For us, 60 years after he published his discoveries, the convulsions of this past year may be jolting us back toward the possibility of being ourselves – being who we and only we were meant to be, rather than functioning as impressive automatons, molded into a standard pattern and working like super-robots, cogs in our organizations’ operations and following the herd instinct. Until now, some of us may have allowed our calling to define us too much, and that, to the degree we have allowed it, has dehumanized us and depersonalized us.

To the extent that we have allowed ourselves to think about it, at least on the edges of our understanding we have realized that we could have been the patients struggling to breathe under the weight of a coronavirus elephant on our chest. Our deaths could have been wrapped into the COVID-19 mortality statistics. More likely than that (because now we know that the likelihood of a working-age person dying primarily of the coronavirus is very, very slim), we could be the ones let go from the workforce due to downsizing. Some of us have already experienced some of this or witnessed it firsthand. All this can dull the allure of a profession and cause us to wonder about our personal futures and the fate of those we love and esteem.

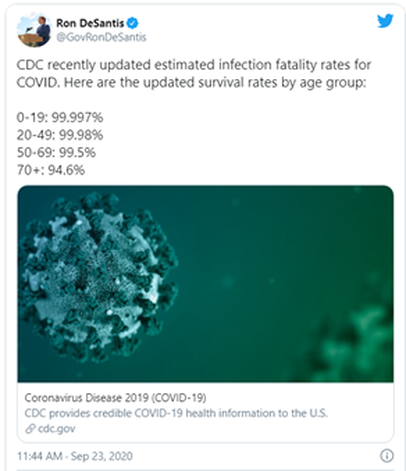

Further, during this past year each of us has experienced the power of the State to control us. There has been a trend, which some have noted as dangerous, away from more democratic deliberation in matters affecting our personal lives, moving toward more of a technocracy – the rule by “experts” who are not clinical doctors but more typically bureaucrats without any particular expertise for judging matters of personal health. In just eight months we have seen the greatest explosion of global fear and panic in world history. Some analysts perceive evidence that this has not been a spontaneous occurrence, but that it may have been “a well-planned, … highly orchestrated …strategy to move the whole world toward people-control and dictatorship.” [5] It is apparent now--to some observers--that fear on the part of the populace has facilitated over-reach by government entities, even though the Centers for Disease Control reported that 94% of the people who were said to have died from Covid alone did not die from Covid at all; they had, on average, 2.6 other co-morbidities.[6] Because of huge financial incentives, hospitals are pushing medical doctors to state the coronavirus as the cause of death in cases where that was patently not the primary cause of a person's death.

Due in part to various degrees of global paralyzing fear and panic, most people have been quite willing to adopt intrusive new habits and relinquish many personal freedoms, hoping that by obeying the edicts of the authorities they and their loved ones would be spared an early death. The new CDC evidence does not seem to have altered those behaviors or those edicts—at least not yet.

We all are suffering—some much more than others—from the (some would say, irrational) orders that have abraded our relationships and threatened our emotional wellbeing. Each of us must decide where the authorities’ boundaries end and where our personal values assert themselves, as public health decrees cross over into the areas of personal rights and responsibilities. In the past seven months we have experienced the results of a historically unprecedented worldwide expansion of government control of personal behaviors. When it involves the quality of the air we breathe (trapped in our masks), or what is inserted into our noses (testing) or injected into our bodies (vaccinations), we each have to think about what the red lines are for us—and what that will mean regarding our ability to continue our chosen work. There is something deeply and disturbingly irrational about being required to keep one's nose and mouth covered for one or two hours while inside one's own vehicle that is being serviced, but on the same day in the same community boaters on a large deep lake where a man recently drowned can be out on the water without wearing a personal flotation device. So far, three times as many people in La Plata County of Colorado have died this year from suicide or accidental drowning than were killed by the coronavirus, but nothing was enforced to protect individuals from those causes of death.

Part One end notes:

[1] Alan Fadling, An Unhurried Life (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2020), page 51.

[2] Ibid., pages 115-116.

[3} Ben Sasse. Them: Why we hate each other and how to heal (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2019), pages 62-65.

[4] Paul Tournier, The Meaning of Persons (New York: Harper & Row, 1957), page 32.

[5} McAlvany Intelligence Advisor, Sept. 2020, pages 1 and 7.

[6} Tyler Durden, “The State's Response to this `Virus/ Is Nothing More Than a Weapon of Mass Submission,” viewed 9/29/2020 at https://www.zerohedge.com/geopolitical/states-response-virus-nothing-more-weapon-mass-submission

Each and every one of us was, in effect, writing our own versions of this article for most of the year 2020. How is it possible to achieve a new and improved balance between the demands of work and the broader realm of all of life?

I started preparing this topic midway through 2019 – Before Coronavirus. From here on, it seems likely that we all will be viewing every aspect of the recent past in terms of whether it was before or after the perplexing and convulsive worldwide events that started to shake our world by early 2020. This choice of topic, which the NAGARA committee selected for an October 1st webinar presentation prior to all that, has seemed more apropos with every passing day.

Never in our lifetimes have we seen the reset button hit in the way it was in 2020. This forced us to stop and readjust our lives. We do not work the same way, our daily routines have been revolutionized, and our sense of what really matters has been sharpened. Never in the history of the world have so many millions of people been compelled to not work, and, in the case of many individuals in some countries including ours, been paid to not work.

One of the positive results of the Covid-19 situation has been a simplifying and decluttering of some aspects of life. We are staying home a lot more, traveling a lot less, and fewer of us have been employed full-time. Perhaps (like me in the middle of this year), you received orders to not work quite so much.

The boundaries of our seashore have been more firmly established than they were the year before. Some protective breakwaters have been established, and more are under construction. Also, we have had to eliminate a lot of things that are not now considered essential. And perhaps there has been some excess that needed to be trimmed away, at any rate.

Some of the aspects of this change have had their benefits, but a lot of it has been difficult—more so for some than for others. The suffering has been real, and the impacts have been bewildering and longstanding. All of this ties in to our topic: how to achieve a work/life balance.

The following four points are the essence of what we will consider in this regard:

• 1. Each of us has a deep need for a full life, rest, and long-term meaning.

• 2. Most of us, much of the time, we cannot maintain a daily work/life balance.

• 3. We can engineer a balance that should last for all our days.

• 4. We can adopt practical strategies that apply to archival/records management work within government agencies.

If there is only one point you take from this article, this may be it: achieving this balance starts with my inner self-talk as to who I am. At the core, we are not records managers or archivists. We are individuals who use part of our talents, aptitudes and motivations to make records available to all who need them, who have the right to see them, for as long as anyone may need them.

We can tend to become ensnared by the belief that we are what we do. “What do you do?” tends to be the first question many of us ask when meeting another adult. By that, we mean, “What is your occupation?” That is not always the most helpful question, because the answer may not give us the essence of who this person is. In his book on An Unhurried Life, Alan Fadling wrote that actually, “what we do is an expression of who we are; what we do does not establish who we are.”[1]

Alan Fadling added that people who say, “I’m going to lose myself in my work” are saying more than they realize. Do we really want all the consequences in the following list?

• Driven-ness to achieve

• Narrow time for escape

• Dogged absorption in detail

• Hyper-responsiveness

• Dashed and dented relationships

• Impaired physical health

Would we prefer to fulfil this list, instead?

• Work that uses our talents

• Health-friendly work environment

• Balance of urgent and important

• SMART prioritization of tasks

• Movement built into the workday

• Scheduled time away from work

A healthy person needs hearty work and regenerating refreshment.

While I was doing the research for this topic, a university professor in his early 50s took his own life. He was a gifted educator but had made a number of unpopular statements on social media and had recently settled with the university for early retirement. The half a million dollar settlement apparently did not mean much to him. His identity, it seems, was so tied to being that professor, and his dismay at how unpopular his views had made him after 20 years in that role was so great, that he apparently thought he could not carry on. His is perhaps one of the most extreme examples of the effects of a work/life wobble, stemming from a lopsided view of who we are. It can be instructive to us.

A healthy person needs the balance of hearty work and regenerating refreshment. This is not at all the same as driven achievement and narrow escape time.{2} We are fortunate, I think, in that most of us like the work we do, and find it rewarding. U.S. Senator Ben Sasse of Nebraska wrote a book last year, Them: Why we hate each other and how to heal, in which he cites research documenting that to be happy, people need to be doing work that matters. In particular, we need to be doing something that benefits others, not just ourselves as the worker. He noted that this is one of just four things humans need, for being happy.[3] Isn’t that why we often go the extra mile to assist a researcher, to provide information that will just “make the day” of someone else?

Thus, our work forms an important part of our personal identity, but we are much more than what we do. The recognition that each of us has a uniquely designed all-encompassing personal identity is the key to achieving a work/life balance.

Paul Tournier, a Swiss physician whose career was focused on helping individuals via a wholistic approach, wrote a book in 1957 called The Meaning of Persons. He wrote that “We are the slaves of the personage which we have invented for ourselves or which has been imposed on us by others.”[4] Our schooling, our credentialing, and the workplace behaviors that will earn us professional success and acceptance by our colleagues have been shaping the roles we act. They have in fact made us, in part, who we are today.

As Dr. Tournier saw so many decades ago, our individual personhood has been eclipsed by the persona we must present in our professional work. For us, 60 years after he published his discoveries, the convulsions of this past year may be jolting us back toward the possibility of being ourselves – being who we and only we were meant to be, rather than functioning as impressive automatons, molded into a standard pattern and working like super-robots, cogs in our organizations’ operations and following the herd instinct. Until now, some of us may have allowed our calling to define us too much, and that, to the degree we have allowed it, has dehumanized us and depersonalized us.

To the extent that we have allowed ourselves to think about it, at least on the edges of our understanding we have realized that we could have been the patients struggling to breathe under the weight of a coronavirus elephant on our chest. Our deaths could have been wrapped into the COVID-19 mortality statistics. More likely than that (because now we know that the likelihood of a working-age person dying primarily of the coronavirus is very, very slim), we could be the ones let go from the workforce due to downsizing. Some of us have already experienced some of this or witnessed it firsthand. All this can dull the allure of a profession and cause us to wonder about our personal futures and the fate of those we love and esteem.

Further, during this past year each of us has experienced the power of the State to control us. There has been a trend, which some have noted as dangerous, away from more democratic deliberation in matters affecting our personal lives, moving toward more of a technocracy – the rule by “experts” who are not clinical doctors but more typically bureaucrats without any particular expertise for judging matters of personal health. In just eight months we have seen the greatest explosion of global fear and panic in world history. Some analysts perceive evidence that this has not been a spontaneous occurrence, but that it may have been “a well-planned, … highly orchestrated …strategy to move the whole world toward people-control and dictatorship.” [5] It is apparent now--to some observers--that fear on the part of the populace has facilitated over-reach by government entities, even though the Centers for Disease Control reported that 94% of the people who were said to have died from Covid alone did not die from Covid at all; they had, on average, 2.6 other co-morbidities.[6] Because of huge financial incentives, hospitals are pushing medical doctors to state the coronavirus as the cause of death in cases where that was patently not the primary cause of a person's death.

Due in part to various degrees of global paralyzing fear and panic, most people have been quite willing to adopt intrusive new habits and relinquish many personal freedoms, hoping that by obeying the edicts of the authorities they and their loved ones would be spared an early death. The new CDC evidence does not seem to have altered those behaviors or those edicts—at least not yet.

We all are suffering—some much more than others—from the (some would say, irrational) orders that have abraded our relationships and threatened our emotional wellbeing. Each of us must decide where the authorities’ boundaries end and where our personal values assert themselves, as public health decrees cross over into the areas of personal rights and responsibilities. In the past seven months we have experienced the results of a historically unprecedented worldwide expansion of government control of personal behaviors. When it involves the quality of the air we breathe (trapped in our masks), or what is inserted into our noses (testing) or injected into our bodies (vaccinations), we each have to think about what the red lines are for us—and what that will mean regarding our ability to continue our chosen work. There is something deeply and disturbingly irrational about being required to keep one's nose and mouth covered for one or two hours while inside one's own vehicle that is being serviced, but on the same day in the same community boaters on a large deep lake where a man recently drowned can be out on the water without wearing a personal flotation device. So far, three times as many people in La Plata County of Colorado have died this year from suicide or accidental drowning than were killed by the coronavirus, but nothing was enforced to protect individuals from those causes of death.

Part One end notes:

[1] Alan Fadling, An Unhurried Life (Downers Grove, Illinois: IVP, 2020), page 51.

[2] Ibid., pages 115-116.

[3} Ben Sasse. Them: Why we hate each other and how to heal (New York: St. Martin’s Griffin, 2019), pages 62-65.

[4] Paul Tournier, The Meaning of Persons (New York: Harper & Row, 1957), page 32.

[5} McAlvany Intelligence Advisor, Sept. 2020, pages 1 and 7.

[6} Tyler Durden, “The State's Response to this `Virus/ Is Nothing More Than a Weapon of Mass Submission,” viewed 9/29/2020 at https://www.zerohedge.com/geopolitical/states-response-virus-nothing-more-weapon-mass-submission

Part Two: How information professions are specifically challenged re: achieving a work/life balance

We will now look at the more practical aspects: strategies for achieving the work/life balance.

First, let us consider how this topic specifically impacts us as information professionals. The human component is the driver for all of our work and for the mission of government organizations. Much as we may enjoy organizing data and categorizing information, arranging things marvelously, all of that work is futile if nobody uses it.

People gravitate to one of these three types of jobs: working with people, working with ideas, and working with things. Our kind of work tends to have us transitioning freely amidst those three. Our work has seasons when it settles quite strongly on one or the other. In the tasks most of us do most of the time, we are most prone to be working with things (physical and/or electronic documents, HVAC systems, computer equipment, storage systems, database manipulation, etc.) but even in those times we must keep in mind the other two categories of work: the people we work with and serve, and the ideas that govern how we should do our work optimally.

In our line of work, it seems that relationships are what suffer most often from our lack of balance. This has been affected, both for good and for the worse, by our working remotely this year. It has sharpened the intensity of our relating to the persons who are nearest and dearest to us. These—not the people at the office downtown—constitute our real family, and now we have had this experience of testing the real quality of our patience, forbearance and love.

On the one hand, the trials of 2020 handed us times of retreat from the demands of work, which can equip us to feed the relational aspect of our lives. On the other hand, the restrictions imposed on our lives are having deep, lasting and deeply negative, psychological impacts. Much of our communication outside our household has become virtual—which means it has been stripped of the nonverbal cues that are the underpinning of good communication.

Mask-wearing orders, for instance, have cut into our ability to relate—because we cannot see each other’s facial expressions. Most of communication is non-verbal, and most of that is from seeing faces. The result is that we have become handicapped in terms of being able to understand one another.[1] This is affecting our work effectiveness as well as our personal lives, and each of us has to find our way back to wholeness in this respect.

One small practical way to build relationship, now and in any era, is to take time out to write thank-you notes to co-workers (and not just on holidays or job evaluation time or when we are switching jobs—and not just by sending quick and easy emails, encouraging as those indeed are). Another idea for strengthening our relational component is to think of the recipient of the email you are drafting. We can be grateful for that person, appreciative of the uniqueness of that individual. Harboring thankfulness is a good start toward restoring balance in our lives at work.

We are living at the tail end of the decades-long juncture of physical records and the electronic, and it is a recipe for a workaholic. Both types of records feed on the other, making it possible for us to do more and more to improve the accessibility of records.

Here are some of the obvious pros and cons that face us every day, that affect our work/life balance. Technology has filled the crevices of our days, accelerating our pace and allowing us much less downtime. We can fit more and more tasks into a given amount of time—and so we do. Often, like hamsters in the wheel, we like to do it. I would venture to say that—for most of us—doing a detailed, repetitive computer task ad nauseum is not nauseating to us. We want to stick at it until it is done. We have decided (internally, and often subconsciously) that we love the kind of work we do, so to us it is not really work and we do not mind putting in more hours than we are being paid to do.

The problem is, a filled-to-the-brim life drains the person who succumbs to it, if that person does not take breaks from this personally impoverishing style of work.[2] Also, it is probable that at least some of what we have slaved away to produce won’t amount to a hill of beans in the long run. Just think of some of your projects from years ago…

One practical strategy in this regard is to take more frequent steps to unplug from electronic devices and return to the real world. I know a man, a nationwide public speaker, who recently died of brain cancer. In one of his last public talks he described how he thought his nearly constant use of cell phones had contributed to his fatal illness. No previous generations experienced this level of electro-magnetic bombardment; there is no long-term track record to confirm the safety or the level of danger of this personal technology.

There are specific nodules in the Records Management/Archival workplace where our potential stressors lurk. Here are five of them:

The first one, which we have just covered, is that our work tends to have an infinite aspect, and we tend to let ourselves be drawn into the allure of doing the best possible job, no matter how long it takes us. Extraordinary events like those of this year can be helpful to teach us that not every aspect of our work can, should or will be done to the same degree of excellence.

A second potential stressor, which I think is seldom off of the screen of our radar, is the inherent ephemera fragility, fluidity and “baffleability” of electronic records. Unlike hard copy records, which will sit nicely in their boxes in their secure storage environments for decades on end, electronic records pose multiple challenges. They must be migrated at some point when the changes in software and/or hardware are about to send them over the cliff of obsolescence. And they must be protected—they could be purged or corrupted in huge quantities without even being missed (for a while, at least). How can any records manager or any archivist stay on top of this for an entire organization?

A third stressor, which no doubt will become much more significant if the economy tanks, is the lack of popular, general support or recognition for our work, and the drop in public funding for it. We have all witnessed the anti-historical protests that came on the heels of the coronavirus emergency this year. Vestiges of the past that contradict the current rhetoric are being toppled and pushed out of sight. People gaining their news from the popular media are seeing a lot more of anarchists than of archivists. The arcane challenges of how to do some of the detailed aspects of our records management work fade in importance when we start to wonder whether the historical cultural evidence will be allowed to survive. The compounding financial repercussions of the coronavirus emergency will, no doubt, make it more and more difficult to justify the inflated annual maintenance charges for our various records management electronic systems, for example. Staffing for basic archival functions is also likely to be endangered.

This lack of support for our basic records functions is sometimes showing up within our organizations. We often have a different ranking of the importance of records preservation, records access, secure storage, and research support than the top officials in our organizations or, even, the people we ultimately serve. This, too, makes it difficult for us to maintain a stable balance between work and other aspects of our lives—because we have to do both what they want and also what we know we must do.

Open records requests are a fourth stressor for many of us. Because of the exponentially increased volume of the electronic records, we have set ourselves up for this stressor. A simple informational request may have to be answered by our providing thousands of emails, each of which may have to be vetted by its sender or recipient and by the organization’s attorney before it can be provided to answer the request.

Part Two end notes:

[1] “Why a Mask is Not Just a Mask,” Columbia University Global Mental Health Programs, viewed on 8/27/2020 at https://www.cugmhp.org/five-on-friday/why-a-mask-is-not-just-a-mask/

{2} Fadling, p. 12.

Part Three: Life has its seasons

Balance may be impossible to achieve on a daily basis, every day, but it is achievable over time. Alan Fadling observed that “Good work grows best in the soil of good rest.”[1] He also noted that a driven lifestyle can become exhausting and unfulfilling.[2]

Here is what we are up against: Paul Tournier observed that overwork can weaken our physical resistance to sickness and disease and can actually cause hardening of the arteries.[3] He reported that “People who are driven, who tend to be workaholics, are more prone to developing arteriosclerosis.”[4] Each of us needs time for the cisterns of our beings to be replenished so we can do our next work vigorously, imaginatively and sensitively—and with renewed focus.

We can, in the general scheme of things at least, reject the tyranny of the urgent. Instead, we can choose to live with the conviction that we have enough time to do everything that is good and necessary. “`If we refuse to rest until all our possible work is finished, we will never rest until we die’.”[5]

When will you be done?

Perhaps you have heard the Pope's famous question to Michelangelo (cited in The Agony and the Ecstasy): “When will you make an end?” The artist replied, “When I am finished!” The German philosopher Goethe, near the end of his long life, quipped that he still had so many unfinished ideas to accomplish, he just knew there is an afterlife for all of that.

Weekly periods of rest and seasonal longer breaks from our work can liberate us from the compulsion to finish it all (in this life, at least). Last September, 39-year old virtuoso violinist Hilary Hahn, mother of two children, has been taking a one-year sabbatical (that ended yesterday) from performing concerts. At the start of her time out she commented that she “didn’t do anything particularly adventurous on my last one, six months in 2009, but none of it was what I’d predicted beforehand … yet it was life changing.”[6] Could you take a break from the thing that makes you, you?

Three ancient peoples offer a model that illustrates this point about the importance of taking time to rest and refresh.

Members of a tribe in South America would march for a long period and then abruptly stop to sit and rest. When asked why they did this, one of them explained that they needed the time to rest so that their souls could catch up with them.[7]

The Bushman of the Kalahari are an ancient little people of Southwest Africa, nearly extinct as a result of their contact with the wider world. Their lives came to popular light worldwide a half century ago as a result of the work of Laurens Van Der Post and others. He described the essential difference between the Bushman and most of the rest of us: “The Bushman is; Europeans and Asians have.”[8] We have possessions, cash, credit, degrees, resumes, initials after our names, birth certificates, etc.; the Bushman has (or had) an acute awareness of their environment, their creation story, each other, and themselves.

One could make the case that the Bushman’s sense of identity is (or was) more akin to that of God, Who introduced Himself to Moses as “The Great I Am” (not “The Great I DO” or “The Great I HAVE”). Van Der Post observed that we don’t really “see” a person until we view him or her through the eyes of our heart—and he adds that we come to really know that person—anyone, really—through a kind of wonder that he or she provokes in us.[9] Until we have that wonder at the awesomeness of a human being, we remain psychologically blind.

The children of Israel, a third ancient people, have prospered in a myriad of ways despite a nearly perpetual state of being persecuted. In part, their blessing has been a result of hearing the 4th Commandment, which is as much a positive command to work six days a week as a command to cease work on the seventh. The 4th commandment is the definitive seminal written statement of the balance between work and the rest of life (literally). It is the longest and most detailed of the Ten. It lays out when to do all the work (“six days”) and when to rest (one day a week). This established the basis for the work ethic of the world’s three main monotheistic religions for thousands of years.

Goals are important in achieving this balance—though they are not the end all and be all. Having exciting (or at least interesting) projects to tackle is what gets us out of bed in the morning. Having realistic expectations helps, too, as does hewing to your priorities. We probably all know the acronym SMART: Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Realistic, and Timely.

The ongoing process of setting goals –both long term and short term – is one of the first steps to success, because the process determines our focus and our desired end state. This can help to keep us from turning aside after empty things that cannot profit or deliver for us.[10] We do not need to be harnessed and driven by our goals—there is a place and a time for doing a task that we had not even thought of doing that morning—but if we have written down our goals, we are less likely to fall into a kind of temptation many of us have (and I speak for myself here) of frittering away our work energies on details that don’t really matter.

Day to day prioritization of our work helps to propel us into our next steps forward. It can spare us from procrastination, and from the sapping effects of carelessly filling our work days with unfocused activity—and also might be good at crowding out our tendency to try to tackle more than we can do. We never really will have the strength or the time for work we are not supposed to do; at least, that has been one of this writer’s life lessons. Overworking can sabotage our long-term work viability.

Here are some examples of worthy long term goals. One worthy long term goal would be to extend the influence of my professional work. Another could be to build multiple income streams, personally. A third goal could be to manage my domain better—the realm that I do control. That could be as simple as organizing my personal papers and documents, video recording the contents of my home for security purposes, planting and tending and harvesting vegetables in a greenhouse I built from scratch; the possibilities are endless and most of us have more time available now than we ever did before.

This writer’s imperfect pattern … a work/life imbalance:

This has not (always/ maybe ever) been a success story for me; maybe it is the same with you? Have you had times—maybe years—maybe decades! when work took over? I sure have. Still do, sometimes! My immediate family can attest to that. You know how some parents have sweet recordings of sweet things their children said when they were very young? Well, I have recordings of phone messages in which my daughter (prompted no doubt by her mother) was declaring how late the hour was, and could I please come home so she could see her daddy before she had to go to bed—especially since he would leave for work before she even woke up the next morning.

I had my rationale (don’t we all). The key phrase was, “I’m just trying to get things done.” I was on the grant hot seat at first, and then on the tenure-track hot seat – and thought I had to make a great amount of progress building the archives, otherwise I would be unemployed and we would be starving (or to quote the dog-eared sign of a young man who is a fixture outside our Durango health food store, “happy but hungry”). Plus, I liked doing it; nobody before me had ever organized the roomfuls of records the college had acquired. My satisfaction was complete when I could appraise, pitch, and selectively organize the mountains of materials. I kept track of my hours and got them back when the department would let me work flexible hours—but the spokes of the wheel of my work/life balance were all out of whack. The problem was, there was more to do than there were hours in the day, and I was not adept at drawing my boundaries.

Losing more than a thousand hours of paid time off when I left the college is another thing I regret. It was sick leave, and when I could have used it over the years, I went to work anyway, because “ I just had to get things done” for 18 years, working from the basement up to establish the college archives and the special collections program, teaching, supervising, and getting us into the new building I helped to design. The obvious lesson: use all of the leave your employer provides, and don’t wait to the end to do so.

We are not alone. Thomas Edison, Albert Einstein, and countless others probably did not have balanced lives. Tying the topic specifically to RM/Archive work, we all can picture examples of persons who have been models of balance in our professional world. Models that have served as reminders to me for many years have included Frank Burke of NARA and of the University of Maryland History and Library Science master’s program in the late 1980s, and Jeff Kintop, formerly the State Archivist of Nevada.

Those of us who were privileged to have been influenced by Dr. Burke knew him as a gentleman in the best and purest sense of the word, and that in part was due to his ability to relate personably and to keep the main thing the main thing. If you were writing the final exam in his class and he had decided that your work thus far showed that you had mastered the content of that course, he might quietly inform you that you could stop taking the test.

I met Jeff Kintop nearly 30 years ago when we were in a Society of American Archivists Preservation Management Program that met several times in Palo Alto, and I later visited his workplace when passing through Nevada, where he had a succession of top positions in the state library and archives. He had a marvelous balance of work and life, and gave his family the time they needed and deserved after he pulled the door shut on a full day of work in the archival world.

Abraham Lincoln is a surprising example of a person who had, in some fundamental respects, a work/life balance—even during the wrenching years of the Civil War. As Doris Kearns Goodwin shows in her book, Team of Rivals, President Lincoln always—even in the most trying times of his presidency, and of the Republic—found time to affirm and listen to individuals of all ranks and demographics. [11] The examples of that would be an article of its own. Lincoln held no grudges and was quick to forgive—and that is an element of achieving a work/life balance. Here are just a few:

To relax, unwind and chat on an evening after a huge day, Mr. Lincoln often would walk across from the White House to the home of Secretary of State William Seward, who himself never quite got over Lincoln’s defeating him for the presidency. (By the way, we heard another famous example of such a friendship, this past week, in the recollection of the unlikely friendship of the late Supreme Court Justices Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia.) [12] Also, as a side note: President Lincoln, unlike Secretary of State Seward, could relax without using drugs or alcohol.

Even on the morning of the Battle of Bull Run (the first major battle of the Civil War), Lincoln made time to be in church.

Ironically (and not necessarily supportive of the theme of this article; work isn’t always the safest place for us to be!), Lincoln’s assassination was while he was “off work,” to watch a play at Ford’s Theatre, as he often had done. He was not shot while he was visiting a battlefield, or while welcoming many hundreds of visitors at White House social open houses, or while making a public speech.

Looking broadly at this aspect of living the seasons of life's balance, it is similar to life in the middle spine of Colorado: between the Rocky Mountains and the plains, we understand that there are times for exhaustion and refreshing exhilaration on high, and times for dogged quiet detail work on the level. One without the other would not be nearly as satisfying or as productive.

Part Three end notes:

[1] Fadling, p. 50.

[2] Fadling, p. 116.

[3] Tournier, p. 147.

[4] Fadling, p. 51.

[5] Fadling, p. 122, quoting from Sabbath, by Wayne Muller.

[6] The Violin Channel, Sept. 3, 1918, article viewed 9/14/2020 at https://theviolinchannel.com/violinist-hilary-hahn-to-take-year-long-sabbatical-from-performing/

[7] Fadling, p. 15.

[8] Laurens Van Der Post, The Heart of the Hunter (San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1961), p. 138.

[9] Ibid, p. 130.

[10] Paraphrased from 1 Samuel 12:21.

[11] Doris Kearns Goodwin, Team of Rivals (New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks, 2005), pp. 506-507, 510, 515, 588, 609, 665, 661-662.

[12] Richard Wolf, “Opera, travel, food, law: The unlikely friendship of Ruth Bader Ginsburg and Antonin Scalia,” USA Today, viewed 9/29/2020 at https://www.usatoday.com/story/news/politics/2020/09/20/supreme-friends-ruth-bader-ginsburg-and-antonin-scalia/5844533002/

Part Four: Practical changes we can make to tweak our work/life balance

Some aspects of work and life intersect (and rightly so). You may be pleasantly surprised to find that it can be relatively easy to begin systematically incorporating additional lifetime habits and strategies into your workday.

By the way, you may want to take a quick online self-evaluation that will give you an indication of how difficult or how easy change is for someone with your kind of personality. Do an online search for psycho-geometrics; your findings can reveal personal tendencies that can affect your work/life balance.[1] Identifying our innate personal wiring will alert to the ways in which the wheels of our life are apt to get “out of true.”

Now, let us now consider some changes that can help to create a good work/life balance. For starters, we can be thinking about eating and drinking smartly while we are in work mode. We can function much more optimally at work if we hydrate properly and avoid debilitating “food.” Fast foods, sugar and alcohol all decrease resistance to disease.[2] Simple sugars are poison to our system, and weaken the white blood cells’ ability to fight bacteria.[3] “According to Jacob Teitelbaum, MD, `A 12-ounce soda suppresses immunity by 30 percent for 3 hours.’"[4]

So, instead of sodas and candy bars, keep healthy food as near to your work area as is allowed and appropriate. Fresh fruit, nuts, shelled pistachios, a can of organic black beans in water and sea salt that you can eat right out of the can—these can keep you from making poor choices from a vending machine and wasting all that money. Having a stash of bottled pure water near your desk, you can set out four of them and set yourself the goal of having finished them before you leave for the day. (By the way, the key to drinking enough water is to think about drinking half your weight in ounces of water each day. As already noted, coffee and sodas do not count; in fact, they set you back. By the time you think you are thirsty, you are starting to be dehydrated.)

In fact, a key part of staying strong and healthy during the threat of the coronavirus (or any virus, for that matter) is to build a bulletproof immune system, and these are all keys to doing that. Why this information is not out there, ahead of reminders about wearing masks and washing hands, is frankly baffling.

Also, we can move about often and incorporate exercise and rest into our workday. This is good for the brain as well as the body. Vary your tasks, change your pace, and get outside. Take micro-breaks (pause for 10 seconds every 10 minutes), take a breather, stretch, and change your eye focus. Follow the 20/20/20 rule to rest your eyes: every 20 minutes, look as far away as possible—at least 20 feet away—for 20 seconds. Or (and this is another of my true confessions—saying but not doing) you can get down on the floor beside your desk and do some planks.

Getting quality sleep is another important aspect of achieving a healthy work/life balance. Someone has said sleep may be the miracle drug of the 21st century. Some portions of the brain that are responsible for cell growth and repair are more active while we are sleeping. Sound sleep could be an important antidote to a day spent in front of computer monitors.[5] In this regard, I have found it useful to have a small flashlight, pen and paper on my bedroom nightstand, for writing down work ideas that come to mind when those theta waves kick in after we lie down. Once the thought has been scribbled down, I can forget about it and go back to sleep.

If you are a workaholic, sleep deprivation could be a possible casualty of working from home. Sure, you have been told to stay home and track your hours. But what if you get a tremendous idea, and you get working on it, far later than you would have if you were still at the office? This is a practical consideration for achieving a work/life balance in the coronavirus age.

Here is a third one: engage the right brain while doing left brain work. For some of us, that means listening to an online classical music station while doing our more mundane indexing and scanning tasks. One of the mottos of WETA-FM in the Washington, DC area is “perfectly tuned to your workday.” Studies have confirmed the benefit of listening to certain symphonies of Mozart as compared to rock music, in terms of assisting our logical thinking.[6]

Another conscious choice that can help to bring balance to our work is to identify and eliminate false guilt and harmful expectations. Our body, soul and spirit are tightly connected. Wrong thinking can impede good working.

Drawing your work boundaries ties in with eliminating false guilt in the work setting. This applies when, for instance, one of your co-workers in a different area of your organization asks you to “team up with me” to help him do his work. If you have been working ‘til dark on a summer day, and he ended his work hours before you did, it becomes apparent that his need is not your emergency. If you were to accept every lopsided request for “teamwork”—knowing that there would be no reciprocation—you would be doing your own work a disservice.

Yet another important aspect of keeping your work from taking over your life is to practice workplace safety and good office ergonomics. A slip, trip and fall can throw your life into turmoil. Carpel-tunnel syndrome from holding your arms at the wrong angle for forty or fifty hours a week can hurt you so much, you become unable to open the door to your fridge. There are lots of helpful training videos out there on these topics; if your organization is similar to many, you get to watch videos on those two topics every year.

One of the work management tools I have found helpful has been to track my actual hours worked. This has been especially important while working from home this year; it has kept me honest, giving the City all the time it is paying me for managing its records, but also preserving the other hours for personal and family life that can be eroded when the place of work is the same as home and there is no door to shut to leave the work world behind at the end of a day.

Along with tracking one’s work time, we have to schedule the work/life balance. This includes introducing variety into the patterns of the workday and the workweek. Plan ahead—for your personal time away from the job, for times when you will be working remotely, and for high-intensity periods of your work. This will increase your productivity, relieve stress, and thus help you to bevel the inevitable crises of work and life.

Some of the projects I was able to complete from home when the coronavirus shutdowns began were to produce a half dozen institutional histories, using the City’s online minutes and other records that date back to 1881. One of them was the draft of an administrative history of the City’s departments. Another was an eBook containing excerpts from City Council minutes that documented Durango’s responses to past epidemics. A third one was a walking tour of the 158 burials in our municipal cemetery during the time of the Spanish flu a century ago (which actually did cause those deaths).

The point of sharing these examples is that these Covid-era days have been prime time for a person who is a self-starter. You know what can move your records and archives program forward. There has probably never been a more opportune time for getting supervisorial approval to take these forward steps that you may have been considering for a long while.

Another proactive step, along with scheduling your work for optimal balance, is to decide ahead of time your personal non-negotiables and get supervisorial approval of them. These could include days and times you will never be available to work (such as certain religious holidays, for example) and areas of work your personal values would prohibit you from doing (for example, something that your personal moral code holds as improper, harmful, or wrongful). When appealing to your supervisor for these agreements, do it as early as you can (preferably, before you accept the position), and be as flexible as you can to work in other areas and at other times that other persons may not want to or may not themselves be able to.

Another idea, which may or may not work for you, which has already been mentioned, is to not try to make your work relationships your family. It is wonderful to have friends at work, to enjoy the presence of your colleagues, but that is not the same as family.

It is good to know when to quit (for the day, or for good) and move on. Leaving a job in which you invested a lot of your life is one of the most helpful and sobering correctives for being out of alignment in the work/life balance. I have now had five positions in which I was the first and only trained and certified archivist. In each situation I have gone all out—giving it everything I have—to establish the archival program.

I think you will agree that there are several reasons why our flat-out work is a good thing. First, it is personally satisfying to make a difference by our personal contributions. That, in essence, is what history is. History is the study of persons and the effects of the decisions they made and the actions they took. And second and more important reason is that all-out involvement on our part is good for our own personal character development. We must confront ourselves and evaluate how we behaved when nobody was watching, and how we treated other people.

On the other hand—face it—most people care more about their personal needs than about their predecessor at work. When someone else takes over from where we left off, their focus is on how to get through their work-week, not how to express gratefulness for the foundation you laid. They, and especially their customers, do remember how you treated people, but that memory also fades fairly quickly. And whether or not your successors acknowledge what you built there, if it was done well and solidly established your work will in fact continue to help people.

How long has it been since you have taken the gravestone epitaph/obituary test? Have you read a lot of obituaries lately? Have you ever drafted your own? So many of the ones I have read lately seem to grasp at trifles in an attempt to summarize a life – as if the façade that Paul Tournier described still had to be maintained. Perhaps it is a matter of not writing something that could reflect poorly on the person who died; perhaps also it is an attempt to not write anything that would be offensive to someone. We read that this person liked to hike, to fish, to arrange flowers, to watch sporting events. Surely, the profound experiences of each of our lives soar higher and plunge deeper than any of that. How much better to live and do in a way that leaves our loved ones with something substantial to write about, when they have to describe us in a hundred words or less.

Here is a recent example of a noteworthy tribute by NAGARA’s current President, Caryn Wojcik of Michigan, that perhaps sets the standard for us:

NAGARA was saddened to hear of the loss of a tireless champion for archives, Dr. David B. Gracy, who passed away September 26, 2020. Dr. Gracy was known as a mentor for new archivists, a superstar in the classroom and professional organizations, and an archivist who inspired all other archivists. He worked in both the university and government environment as both a teacher and an archivist, serving as director of the Texas State Archives from 1977 to 1986 His enthusiasm, kindness and tireless energy will be missed by the archival world. Dr. Gracy never failed to convince others of the value, relevance, and significance of archives and archivists to all members of society. His colloquial charm and unbridled enthusiasm inspired students and established professionals to push the boundaries of the traditional definition of an archivist. [Because he was] fearless and outspoken, the legacy of Dr. David B. Gracy cannot be understated.

One day, for each of us, the career in which we invested so much of ourselves, and which was so much a part of ourselves, will calve, disintegrate, and disappear into the sea of our hopes, meanings and satisfactions. At that point, the rock that is the essence of our person will still remain—though somewhat smaller than it was before. Part of the challenge of maintaining a work/life balance relates to preparing for this ebbing away of our careers.

It is easy to initiate some changes.

Although (true confessions), I find it difficult to adhere to them all the time, it is quite easy to get yourself moving into these positive changes. For starters, you can begin systematically incorporating lifetime health habits/practices into your workday. These include such basic things as hydration and avoiding debilitating “food” options at work. Those victories are won or lost at the point of purchase. Buy yourself food that will give you a boost. Bring that water bottle to your desk, with good quality water in it. Start recording your actual time worked and what you accomplished. You get the point.

Use the BRAIN test for each aspect of your work/life behavior options. It is an acronym that is helpful for evaluating your course of action in a variety of circumstances.

- Benefits (what good will this do?)

- Risks (what could go wrong?)

- Alternatives (what might be a better way to do it?)

- Intuition (what is my gut telling me?)

- Nothing (what would be likely to happen if I do nothing?)

Part Four end notes:

[1] https://www.psychogeometrics.com/onlinetest.php (viewed on 9/29/2020)

[2] “The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition published a study that found the ability of white blood cells to kill bacteria is significantly lowered for up to 5 hours after eating 100 g of sugar.” Cited in” 7 Steps To Immune System Recovery,” Amanda Pierce, at https://www.homecuresthatwork.com/17069/7-steps-to-immune-system-recovery/ (viewed on 9/14/2020)

[3] “What’s the sugar immune system relationship?,” by Rachel Garduce, April 6, 2016, at https://allnaturalideas.com/sugar-immune-system/ (viewed on 9/14/2020)

[4] “Here Are the Myths About Your Immune System You Need to Stop Believing,” by Allie Hogan, April 3, 2020, at https://bestlifeonline.com/immune-system-myths/ (viewed on 9/14/2020)

[5] Kantola.com training video by Kantola Training Solutions, 2020.

[6] ”Listening to Mozart can boost your memory: Classical composer's music increases brain wave activity - and it beats Beethoven,” by Sophie Freeman, June 5, 2015, Daily Mail, viewed 9/14/2020 at https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-3112339/How-listening-Mozart-boost-memory-Classical-composer-s-music-linked-increase-brain-wave-activity-beats-Beethoven.html

Part Five: Two physical analogies in conclusion:

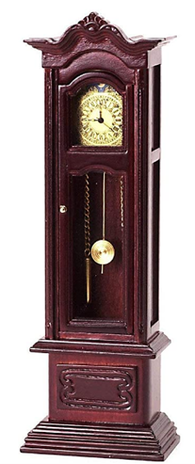

Before we draw to a close, I want to leave you with two images to reinforce the thoughts of this past hour. The first is a pendulum eight-day chime clock. Think about its parallels with our achieving a work/life balance. Here are seven. You may think of more to add.

- It must be wound by hand, every 7th day. If you do not wind it up, it runs down and enters a state of listless un-performing un-useful entropy. Winding it is an intentional choice on my part, not automatic. Over-winding it, though, could break the clock.

- It has a steady pulse—a constant rhythm—if the clock is in correct vertical balance. Tilting it to one side or the other makes the pendulum swing too far to one side and not far enough to the other, and it will not keep up.

- Though it has a pulse, it has variety in its day. One of its hourly chimes (1 pm or 1 am) is single, but another is 12 chimes. Some hours have much more packed into them than others. The quarter-hour rings of a Westminster Chimes clock keep the hearer on track (“this quarter hour is gone!”)

- Some clocks’ pendulums are longer and/or heavier than others, and have a wider sweep than others. The lesson here is, do not try to be someone else’s clock; the pendulum is proportionate to the hands and overall size of the instrument.

- Clocks’ hands must be moved forward, or halted, to regain equilibrium and reset the time. Turning the minute hand backwards may loosen the device. We move forward, not backwards, though sometimes we have to stop and regroup.

- Occasionally it is good to stop the pendulum, to silence the clock so you can focus interrupted on an important thing for a while.

- Sometimes a clock’s mechanisms are dirty and need to be cleaned and oiled. I think the parallel with healthy personal living and refreshment is obvious.

The second image is of a slide puzzle (pictured below), which gives us reminders particularly regarding our career lessons.

- First—and the whole time—know the big picture and keep recalling it as you work

- Keep on working the puzzle

- Do not get hung up on having to do it perfectly

- Bear with the process

- Accept that things may look worse as a result of your efforts…until the end

- The timing of the arrival of the end is usually a surprise, when it all comes together

- Give yourself the most optimal work environment possible

- Work on a flat surface

- Do what you can to help the project slide along better

- Look for clues

- Get external help if you can find it

- Pace yourself

- There is more to your life than this puzzle

- Know when to take a break

- Do not take it more seriously (in the larger scheme of things) than it deserves

- This—like much of life—is not rocket science

- Perseverance, patience and creativity can take you a long way

- So will kindness and patience (“No, you go first, please”)

- Try to enjoy the process; do not fight it

- This too, shall pass

In conclusion: in some strange ways we are fortunate that we have been forced into this period of re-set, a long span of time in which we can re-evaluate and re-purpose our living. As information professionals in particular we are fortunate to have lived in this sliver of history that is bridging the physical and the electronic records. Perhaps the convulsions of our day will do us, and our profession, a great deal of good, as we re-shape our work/life balance and re-tool to live for what truly matters most and truly impacts our world in a way that only we can do. If this catastrophic worldwide situation does not bring us to face this, what would it take for us to finally see it?

~~~~~~~~~~

If you have found this presentation online at archivetools.weebly.com you are also on the site where I have also posted a free 11-week basic self-paced introductory course in archives that has been seeing a hundred or so unique visitors a week during the worldwide crisis in 2020.