11th section of the course: First section

#11A

This course at last becomes personal

to make sure you obtain something workable,

just to make a new living

or to use what you're making

with skills that are organizational.

XXII. Careers in archives and records management

- read "'Dear Mary Jane': Some Reflections on Being an Archivist" by John Fleckner, "Making History Pay" article by Lisa Gubernick

- read Arlene Schmuland's online suggestions for landing "That elusive archives job"

- check out the Society of American Archivist's SNAP Roundtable, focused on students and new archival professionals, which includes "Ask an Archivist" where you can anonymously request advice from a volunteer panel of experienced archivists

- look at the jobs advertised on the SAA Online Career Center -- and listed on ArchivesGig and also at INALJ.com (I Need A Library Job), which includes listings of job opportunities for archivists and other information professionals

- read "Open Cover Letters," a site that collects anonymous cover letters submitted by successful candidates for library and archives jobs

A. Some good changes in recent decades: in archival education, more graduate programs in history and library and information science now include regular, full-time archival educators, and the increasing depth and breadth of continuing education workshops, institutes and seminars sponsored by national organizations like the Society of American Archivists and regional ones is a big help to individuals who lack prior training in archival work.

B. Education and training requirements for dealing with different types of materials; certification

Unfortunately, ACA certification still follows the failed (and failing) model of graduate school as the only means of acquiring expertise in a field.

- peruse the Academy of Certified Archivists website and read its manual, which includes sample exam questions. As the manual notes, "Archivists become certified by qualifying for and passing an examination offered annually by the Academy. The exam is composed of 100 multiple-choice questions based on the Role Delineation Document described earlier and appearing in this Handbook."

Pursue alternative means of getting yourself trained and experienced as an archivist. For motivation, read Chucking College and visit the Uncollege site.

C. Alternatives to traditional classroom-at-a-university training

You don't have to take a course at an institution of higher education to learn the theory and practice of being a terrific archivist. Most archivists who had formal education would probably tell you that there were one or two teachers that were invaluable--and that they probably could have learned as much by working with those individuals, one on one. (That was my experience: though my two masters degrees were from a program that was highly regarded at the time, most of what was truly valuable was taught by two instructors who had real jobs during the day: Frank Burke of the National Archives and Karen Garlick of the Library of Congress.) You could spare yourself great expense of time and money by teaching yourself the basics of archival work. Supplement your reading and study with practical experience as an apprentice with an accomplished archivist whom you respect and who is respected in the archival community, and you can jump-start ahead of students who leave college and graduate school unemployed and saddled with huge debt.

- look at the SAA's "Best Practices for Internships as a Component of Graduate Archival Education"

11th section of the course: Second section

#11B

XXIII. Personal applications of archival theory and practice

jokes:

- have you met the woman who wants to have four husbands before she dies? She wants to marry first a banker, then a movie star, then a preacher, and finally a mortician. That way, she'll have one for the money, two for the show, three to get ready and four to go.

- the other day, I was feeling so low, my yo-yo wouldn't even come back to me

A. An archivist’s thoughts on the value of family history

1. A nephew's carpool buddy asked the driver if she knew his dad. "He lives with us, at home!" he said. That this might not seem funny to us is a reflection on a major change in family life during the past generation. But it shows that we still do want these family ties, these roots. And that, to me, is a great part of the value of local history.

2. thoughts on why we should maintain our family records:

a. "For we brought nothing into this world, and we can take nothing out of it." (I Timothy 6:7)

(1) our papers and snapshots are going to burn, decay, get stolen or lost or otherwise cease to exist

(2) there's a broader and more cosmic view of the importance of preserving our personal papers: during a brief time, they influence the shaping of our lives as eternal beings, and that is their true value. There is more to our daily actions than is seen; there's an ongoing character development, which is reflected in the family papers that document our moral choices and significant personal decisions that are shaping who we are. The process of maintaining our personal papers--our autobiography in whatever form--can be healing to us (SEE ARTICLE FROM NEWS).

(3) how many people who are on their death beds remark, "Life's over so fast." Family members who follow us are apt to turn toward our personal histories for a set of values and a heritage which shapes who they are.

(4) even if we or anyone else never consults our papers, they are part of a personal foundation of identity.

b. as we attempt to understand ourselves and our surroundings, our view of time is key

(1) an understanding of our personal past enables us to be facilitators of the future, rather than just being custodians of the past. In shaping the future course of our lives, we will be more apt to make a wise choice if we are first informed of previous decisions--by our community's political, business, educational, social, and spiritual leaders and by its individuals--whose decisions have led to this one.

(2) as the contemporary Christian writer Philip Yancey has observed, there is a sense in which we, like God perceive time in a never-ending present. Unlike God, for us it all happens as a sequence of events. Nonetheless, "we do all our thinking in the present. ... Because I only exist in the present, I can only perceive the past and the future from the perspective of the present." (Disappointment with God, 1988, p. 235)

c. thus, the past is not something we can box up for posterity. Even the archivist's document case is a factor of the present. Decisions about what parts of the historical record to place in that box and which to discard are present decisions, ones which are likely to be re-evaluated in a future present.

Archives is the oldest profession; Adam's task was to name all of the created beings, and thus to control them and live peaceably among them (Gen. 2:19-20).

B. Personal records management -- tips for filing your own documents:

1. have a designated place for everything you want to preserve and access

a. a labeled folder or envelope for each type of record/for each person, current records

b. do it! - don't put it off into an unsorted pile; small attentions at the first moment you handle an item will save you time and frustration in accessing it later; open your mail next to your filing system and your trash can

2. manage your records; pull the older non-current documents from your active files and place them in their own labeled folders in a box stored off-site, unless they're permanently valuable in which case you will archive them, and pitch those which are not needed for legal, administrative, or sentimental/personal consultation later.

a. it's probably time to move 'em out once a file is 2" thick or more

b. choose storage units that suit the size and nature of your records -- i.e., is your filing cabinet letter size or legal size; folded papers will eventually crack and will double the required filing space

c. create a paper trace; pay your bills with a check or credit card, and keep filing these records as you receive them

d. basic principle of personal records management: reduce the number of times you must handle each item; try to dispose of each item the first time you handle it; this means that you have established a logical home for each potential item

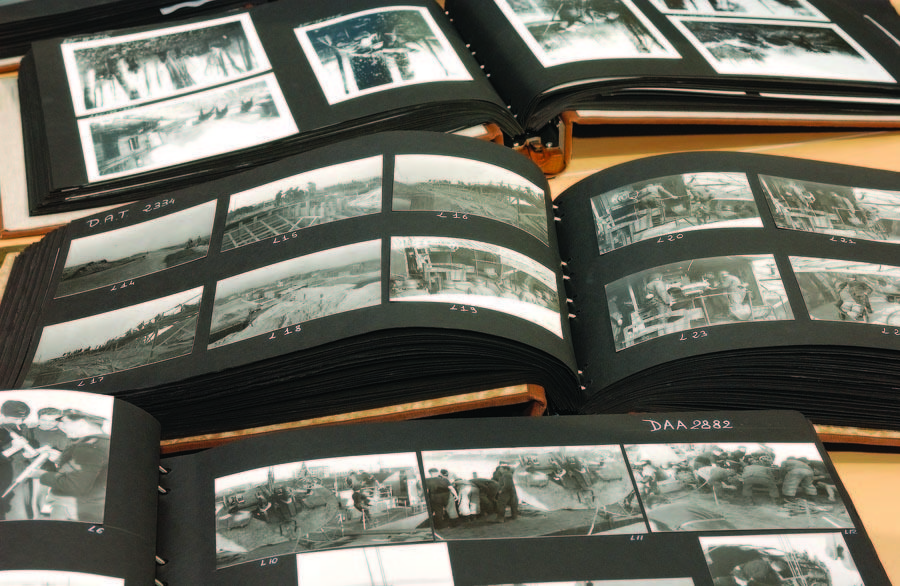

C. Arrangement and description of your photos

1. it began [ideally] when someone brought the processed snapshots or slides home [in the olden days]

2. before showing them around, write (in pencil, sliding it across the back of the print to avoid denting the emulsion) the basic identifying info on the back of the photo:

a. date taken

b. names of subjects, places, events, people, and write the date on the negatives' enclosure and

c. a brief phrase summarizing the topic(s) of the photos

3. preferably, store the photos in a separate building from the prints

4. identify those old photos ASAP; have a party and get it done!

D. Arrangement and description of your papers

1. gather similar types of records together

2. unfold all pages and face them in the same direction in the folder/envelope

3. maintain each file in (usually) chronological order, by filing the most recent additions in the very back (or, if you prefer a reverse chronological system, the very front) of the folder

4. the single most important act in gaining control over your papers is to name them; come up with proper--discrete, harmonious, encompassing--titles for folders, file drawers, and boxes.

- often, fill-in-the-blanks notebooks are useful only to those who profited from their sale; they often sit in a drawer, unused and useless to the busy people who received them.

E. Take stock of the overall environment in which you are keeping your own papers and important records:

1. environmental factors and their effect on constituent materials (review)

a. basically, the same environment that is comfortable for us is good for the materials

(1) temperature

(a) heat from sunlight, heating systems, & artificial lighting accelerates all chemical processes- high heat can desiccate, embrittle, melt, and scorch items

(b) optimaltemperature is as cool as possible, taking into account human comfort, condensation when taking items from cool to warm areas, and air conditioning expense; about 65 degrees is best

(c) temperature should be a top priority

2) relative humidity - has a symbiotic relationship with temperature

(a) physical damage: hygroscopic materials such as paper have the ability to absorb and give off water; paper expands when wet, whereas cloth contracts; the two materials expand and contract in opposition to one another; this causes problems with objects composed of different materials

i) high r/h can increase insect activity

ii) at about 30% r/h and below, cellulose materials begin to dry out--desiccate--and the sheet weakens as fibers break--so low r/h is also a problem

(b) chemical damage: moisture is necessary for some chemical reactions (esp. red rot on leather and hairy mold--at over 60% r/h, the ever-present mold spores are activated, esp. on organic material) and foxing of paper containing iron pyrite), and high r/h intensifies the effects of air pollution and acid hydrolysis

(c) ideal r/h is less than 65%; most people suggest 45% +- 5%

(d) an article in the Feb. 1990 Abbey Newsletter reports that "One estimate made on the basis of research is that the longevity of paper is increased 50% by storage at 30% rather than 45% RH." High RH speeds up the damage caused by light, air pollutants, oxidation and hydrolysis. Furthermore, the climate of the locality sets limits on the achievable range of RH. "In dry, cold climates it may be impossible to push the RH above 20%..., and even if possible it may be inadvisable because of the resulting condensation on poorly insulated windows and walls." There's a lack of consensus on this issue today. For our region, 40% RH probably is a good upper figure.

(e) measured using a sling psychrometer ($65) or with a recording hygrothermograph (drum in a box, turned by clock or battery mechanism, uses horse hair to detect changes in r/h and temperature) or with a thermohygrometer (little dial instrument, useful for exhibit cases; check it regularly against sling psychrometer for accuracy). Michael Barford in NJ sells a Thermo Hygro for $59 which tells you minimum and maximum temperatures and relative humidities.

(f) practical steps: keep the air moving; arrange stacks of shelving parallel with the air flow and away from outside or basement walls to avoid excess moisture from leaks and/or condensation and mold and insects

(3) fluctuations of temperature and relative humidity are the worst; cycling daily and seasonally puts a great internal strain on paper, which is hydroscopic--it expands and contracts in response to changes in moisture; this is esp. a problem when the paper is bound to a more rigid material, causing cracks and flakes

(a) when temp. rises, relative humidity falls, and vice versa, assuming that the moisture content of the air is static, because the air can only hold so much moisture at a given temperature

(b) microenvironments are a recent concern of preservationists: a study conducted by the National Bureau of Standards for the National Archives concluded, among other things, that container can provide protection from the macroenvironment provided that they have not gaps in them; the prototypical container, the Hollinger records storage box, has a hole in each end which results in "diffusion of pollutants through the gaps at a rate that for practical purposes, the container might as well be open." (reported in Oct. 1991 newsletter of The Commission on Preservation and Access.)

(c) light is a type of energy, measured in wavelengths (nanometers); light radiation causes photochemical reactions; the invisible ultraviolet rays (on the shorter end of the wavelength spectrum) can darken or fade paper and make it brittle; u-v radiation comes from the sun (more at higher altitudes) and from unshielded fluorescent lights

i) control light's effects by eliminating harmful ultraviolet rays by keeping out bright sun, using filters, and/or changing the type of light; also, by connecting the lighting system to a motion detector so that an area need only be lit while people are in it (a system noted in the July 1989 Abbey Newsletter uses a computer; it's called Static Lighting, and is available from Richard Spencer in Crete, NE)

ii) visible light also is damaging, because of its intensity and duration (also determined by the type of light)

iii) photochemical damage manifests itself in bleaching (common with rag paper), and yellowing, fading and brittleness (all common with ligneous paper)

iv) effects of exposure to light are cumulative and irreversible, and the energy already absorbed by an object makes it that much more susceptible to further damage

b. airborne pollutants such as dirt and dust (which can cause acidic attacks, "foxing" = little brown specks on paper as it reacts with metallic elements in the paper), sulfur dioxide (car emissions, catalyzed in moisture to form sulfuric acid); insects and rodents like dark and dirty environments

2. biological agents: mold, vermin, insects

a. be a good housekeeper; keep the storage area free of dust, mold, and vermin, and provide an environment inhospitable to them; prohibit eating and drinking in or near the storage area

b. remove infested materials from storage

3. storage, use and handling:

a. storage

b. security = concern about potential damage from people and from the elements (esp. fire)

(1) prior question is, what do you consider the desired lifetime of your materials; whether perceived or not, aging is producing changes in all items, so faster than others

(2) protect the storage area from fire, flood, theft, and intrusion

(a) in 1975, fire destroyed 20 million files on the 6th floor of the federal records center in St. Louis, Missouri; this persuaded archivists to use smoke detectors and sprinklers, and not to shelve Hollinger boxes with the opening lid facing front--files fell out when front burned; loose sheets of paper are more flammable than tightly bound and closely shelved library books

c. housing

(1) use only pH-neutral materials for storage; boxes should be airtight (see above discussion of microenvironments)

(2) housing of manuscripts - two types:

(a) document boxes, storing folders vertically, sometimes using polyester sleeves

i) shouldn't be underfilled or overloaded; don't overpack material on shelves or in boxes

ii) avoid placing acidic materials such as newspaper clippings next to other items

iii) books in boxes should rest on their tails, not on their fore-edges or spines

iv) house your photos in archival plastic

a) test for good plastic: heat copper wire and, using pliers, stick it through the plastic. If it burns bright green, it contains polyvinyl chloride (PVC)

b) PVC is a bad substance which breaks down to form hydrochloric acid and gives off harmful fumes

c) most commonly available photo albums use PVC

v) through the late 1970s, lamination was a popular means of preserving much-used documents: putting a laminate of mylar/tissue/document/tissue/mylar into a heat press that melts the plastic into the document; problem is, document remains acidic, and the process isn't reversible; solution: put item into alkaline solution bath, then encapsulate it in mylar sealed on the edges.

- (source: Colorado Preservation Alert newsletter, Dec. 1991, article on encapsulation by Sharon Partridge): "Encapsulation does for a single page what phase boxes do for books and pamphlets. In addition to protecting the item from the environment, encapsulation makes it possible to handle extremely fragile paper. Placing the document between sheets of inert (chemically inactive, doesn't interact with the paper) plastic sets up a static field which makes use possible. While this does not decrease the brittleness of the paper, the enclosure does prevent further breakage. ... It is better to do any deacidification, mending and cleaning (Scum-X works well for cleaning...) before encapsulation..." {demonstrate encapsulation of an important or fragile document} (may fold Mylar in half and crease, allowing for .5" borders on all 4 sides; double-sided tape on one side touching the fold, leaving 1/8th inch space between paper and tape to avoid migration of the adhesive and likewise between tape and edge of Mylar so external dust and dirt won't be attracted to the adhesive, and when taping the last two sides leave a 1/8" gap where pieces of tape meet at the corners to allow the emission of gasses from the paper as it deteriorates and breathes; use a paper weight to hold the free corner up while applying the tape to reduce frustration; roll from the finished corner to remove excess air and air bubbles) - pre-made polyester envelopes are available.

- in an article in the Sept. 1989 Abbey Newsletter entitled "Not All Mylar is Archival," Tuck Taylor reports that DuPont now makes over 100 varieties of film from polyester, all of which are called Mylar. This includes a form called M-30, which is coated on both sides with polyvinylidene chloride, which over time can break down and give off something like hydrochloric acid. The appropriate form of Mylar for archival work is film that is uncoated, biaxially oriented, with not chemicals or particulates added to the base sheet; Type D is the most recommended form of Mylar for our use. ICI, 3M, and American Hoescht also sell the equivalent of Type D Mylar. The point is, one must do one's research before ordering archival supplies!

- (Partridge, continued) comparison of encapsulation and lamination is indicative of several archival principles: "Lamination, in contrast to encapsulation, is a heat-activated procedure which involves the use of chemical adhesives which penetrate the paper. The temperature required for adhesion is 250°F+ which accelerates the aging of paper and can actually discolor some papers immediately. Also, the plastic used, poly-vinyl chloride, is a culprit in accelerating paper deterioration." Lamination, unlike encapsulation, is irreversible, and is not archival process.

{what archival principles does the comparison of these two methods demonstrate?}

(b) bound volumes, either

i) hinged by cloth on paper along one edge, edge mounted, inset into matting windows (glued on the edges), or solid mounted (adhesive all over the back of the document), or

ii) directly bound into a volume and sewn in, or

iii) laminated and then bound, with the extending laminating strip serving as the hinge; this binding is expensive (esp. to support the weight, to lie flat, open fully, & be acid free), time consuming, irreversible, and the hinge paper and backing material can be incompatible with the document

(3) handling

(a) rough/improper/frequent handling; photocopying; improper storage; misguided repair or restoration

(b) conservation steps must be reversible; with training, in-house conservation can include removing all staples, brads, paper clips, and rubber bands and replacing them with file folders (if further grouping of items is necessary, use stainless steel paper clips under archival paper; even plastiklips are inadvisable, as they can bend and tear the pages); never use scotch tape or glue; use non-abrasive erasers; mend small tears with archival mending tape; encapsulate fragile items in polyester film (mylar)

Reading for next part of this last section:

Modern Archives Reader, ch. 8--"Public Programs."

11th section of the course: Third section

#11C: Last section of this course: Archival outreach

Outreach pulls it all together:

Access, arrangement, and whatever.

Failing this,

it's hit or miss;

your end might come too soon--or never.

XXV. Outreach from archives

A. Outreach goal: "an effective public relations program brings users, donors, and funding to the archival repository" (Julie Bressor, Shelburne Farms, VT., MARAC May 1992 preconference workshop description)

B. Three general areas of outreach (source: SW Archivist, Fall 1992, p. 4)

1. persons who might benefit from using the collection

2. donors and potential donors who might benefit your repository

3. more passive outreach to public through exhibits and other methods

- note: ca. 20% of ACA (Certified Archivists) certification exam pertains to outreach

C. Good thoughts on outreach from the "Archives & Archivists" email list 3‑MAR‑1993, by Dean De Bolt:

"Personally I feel very strongly that outreach has to have personal commitment on the part of each individual archivist to be effective. We have always had fairly traditional outreach programs in the profession; these take the nature of:

1) guides or catalogs to the collections (ranging from collations of abstracts, to detailed catalogs, to individual published catalogs of individual record series)

2) handouts or brochures designed to give users a quick overview of an archives, its collections, hours of service, etc.

3) occasional newsletters where news of accessions, special studies, cases of how the archives contributed to a book, etc.

“These are great and do reach a wide range of user audiences depended on how each of these items are written and distributed. The problems with them is that they are fairly static. If you pardon my expression, they simply lie on the table and are there if the user has them, finds them, or THINKS of them.

“Personally I believe a more dynamic approach is required of archivists. The difficulty is that it requires an on‑going commitment of time and even work beyond the 8‑5 normal schedule. These activities include:

1) speaking engagements‑‑the archivist should be prepared to speak about the collections, but can develop interesting community programs which incorporate publicity for the collections.I offered to do a program for a local history group on the Centennial of the Pledge of Allegiance (got the idea from the LC exhibit); this has now been repeated about three times as word of mouth has spread. At least one new collection has been received from each occasion from people in the audience who did not know about the Special Collections.

2) special workshops‑‑periodically I offer, on a Saturday afternoon, a special workshop open to all on some topic...it might be "How to Use the Collections for Genealogical Research" or "Tips in Preserving Family Papers." I limit enrollment to what space I have, have the University publicize it, and offer it. Frankly, I get no money for this or even compensatory time; the workshops are not required by my superiors. But they engender goodwill and have lead to increased usage, and accessions.

3) collection awareness‑‑in the University setting, I try to send out a special letter to selected faculty in departments to announce a new collection. I also zero in on HOW the materials could be used by their students‑‑‑in short, what research papers could be written? This has drawn students who "have been assigned to write that" and faculty drawn to explore what other materials are available.

4) letters to faculty‑‑I try periodically to send letters to new faculty (sometimes I offer a special date to give them a tour) explaining briefly the Special Collections and asking them to contact me for more information on how they can be used in classes. I also try to send letters to faculty teaching specific courses reminding them of resources in the Department.

“All of these activities (and many more that I try) necessitate time, which I feel pays off in the long run. They have to be tailored to your specific purpose, the audiences you want to reach, etc. For example, if you only have university archives, you may not wish to involve the public. In that case, you could offer periodic workshops for University staff in how university information is available and how to get it.

"As you read my thoughts, you probably know by now that to me, OUTREACH is the embodiment of all activities to make the collections known, to encourage researchers, and to reach donors at the same time. I've found all of these seem to work together. You can, of course, plan specific projects separate for collection development or for user education."

-Source: Dean DeBolt, University Librarian, Special Collections and West Florida Archives, University of West Florida, Pensacola

D. Objectives of a good public relations archivist

1. an effective p.r. archivist turns daily events into public relations opportunities, plans outreach activities that fit institutional and staff resources, chooses and implements the best approaches to publicity in the various formats of the media (print, visual and sound), and knows how to take advantage of bad news

2. outreach activities include: exhibits, publications, education, and public relations

E. Exhibits strategies

1. rationale: exhibit function is written into the legal function description of the institution

2. isn't it a threat to exhibit materials from a collection?

3. two types of exhibits are museum type (artifacts and art) and documentary

(archival records; materials from manuscript collections)

a. museum type exhibit speaks for itself

(1) doesn't require the reading of captions unless the reader wants more details about the exhibited items

(2) object can be spotted from afar, in a space devoted to that theme

b. documentary exhibit items need help

(1) weren't created to make an impression from afar

(2) they're one-dimensional

(3) were created to express a message by being read up close

(4) thus, the added explanations for these exhibits are more important than the items displayed

(5) each item must be enhanced and placed in context by placing it in a story/theme

(6) e.g., after choosing a theme of the Mormons' movement West, one would draw up a chronological/historical outline and write it up; then, practically throw out the narrative and exhibit the footnotes (the most significant documents) and put a big caption over all 4 panels with subheadings for each topic/panel and captions for each accompanying document; add a map, photos, artifacts to mix the media, and have one document lead to another, with sufficient captions that the audience won't even have to read the documents

4. planning placement and format for an exhibit

a. know your audience before developing the theme, type of captioning and documentation, and the intensity of message

b. flat case displays take the least amount of preparation (for security, turn it so the key-hole is against the wall)

c. if many people will be passing through a displayed item must be on a wall where more people can see it, by sandwiching it between UF 3 plexiglass and acid-free matboard

d. add dimension by building vertical cases at variable distances from the wall--like townhouses

e. exhibits in waiting areas

(1) place documentary exhibits in places where people have to wait (by elevators, in waiting rooms)

(2) choose something esoteric

(3) change it often, because people will return often to these spaces

(4) don't overwhelm the reader with information, but show the document with a brief, large-printed intro/caption

f. regular exhibits

(1) people seldom visit archives as tourists

(2) people visit a historical repository about 3 times:

(a) as youth, young couples, and retired people

(b) thus, appeal to wide range of people, though the presentation can be long term (change it every 3 years or so)

(3) not too esoteric (unintelligible) or simple (uninteresting), but

(4) with clear explanations

(5) fairly splashy

(6) info must be quickly accessible and not too detailed

g. exhibits for staff

(1) can be more detailed

(2) must be changed monthly

(3) perhaps continuing the same theme/story as it changes

5. exhibit tips/ display techniques

a. locate exhibits within a person's viewing span (3' to 6' high) F. use the "dead" bottom and top horizontal spaces for color or for bold graphics or transitions

b. vary the media, the textures, and the arrangement

(1) consider multi-media displays (slides, rear screen projector, loop projector, audio)

(2) use islands or cubbyholes for thematic concentrations and to allow for areas of deeper study

(3) use a suitable backing (rustic for the Mormons exhibit; velvet and gold tassels for treaties)

c. don't leave documents on exhibit over a year (light, backing, mounting dust, pollen, either can be detrimental)

(1) temperature fluctuations to save energy in off hours are damaging to documents

(2) fluorescent light is cool, but ultra-violet unless filtered with a tube; incandescent light lacks U-V but gives off heat

(3) southern winter sun was shining on the Declaration of Independence, Constitution, and Bill of Rights in John Russell Pope's National Archives building, until the Archives window was painted

d. Montreal Expo (mid 1960s) led to new developments in museum displays:

(1) some clear ideas

(2) good traffic flows

(a) think about the traffic flow

(b) usually it moves toward the right hand, the same way we read

(3) simply and cleanly communicating

(a) avoid object and information clutter

(b) the goal is to communicate, not to fill your display cases (c) provide handouts for few people who want to know more

e. after planning an exhibit, go through it as a naive viewer; is it interactive? does it communicate the primary and secondary messages?

f. document what you exhibit

(1) take a photo of it (in case someone wants a copy, or you want to reassemble it, or something happens to it), and

(2) keep a case file on the exhibit (accession numbers, dates), &

(3) make sure everything is returned to its proper place when the exhibit ends

6. lending items for exhibit

a. never lend to an institution that doesn't treat the documents at least as well as you treat yours

b. make sure that your institution is credited, & that

c. exhibit is patrolled during hours and alarmed during off hours, & that d. there are heat, humidity and light controls

e. no framing allowed

f. all costs borne by recipient institution, including insurance to cover damage (not loss)

7. summary of general points about display design:

a. begin by deciding your primary message (your secondary message should be self-promotion)

b. know your audience

c. study others' exhibits and consider how they expressed their message

d. know your spacial, physical and financial limitations

e. choose relevant mediums

f. involve the viewer actively at the highest level reasonable

g. heighten the interaction, to complete the communication

h. quality, not mass quantity, is what appeals

G. Publications from archives

1. exhibits assume that the person you are addressing is in your city, your building, and your exhibit area

a. counter this by sending travelling exhibits (with good facsimiles of the documents)

b. or by exporting the intellectual and in some cases the illustrative parts of the exhibit in a catalog

2. the script that you don't exhibit can become the exhibit catalog

a. contains copies of all the exhibited documents plus your notes

b. this can live long beyond the exhibit and be informative apart from seeing the exhibit

3. four purposes of publications

a. information (to educate)

b. inspiration

c. explanation (to inform of items' existence and the institution's reason for existence), and

d. money (to raise funds)

4. publications tips

a. in its graphics, style, photos, calendars, etc., each publication should reflect the nature of the institution and the subject, and

b. should aim at broadening the institution's scope rather than being limited by it

c. publications can be effective without being expensive

d. imagination and style go a long way

e. use clear, bold cover graphics

f. largest print on cover page should convey most important information

g. use the same/similar logo on every cover for corporate identification

5. brochures are useful

a. can substitute for letters for regularly requested basic information

b. should fit into a standard #10 envelope and be light enough to mail under 1 ounce

c. clearly giving the institution's name, address, and hours

6. next step: folder of separate pages which are facsimile copies of significant documents

a. on paper and sizes that makes them look like the originals, but

b. bearing a tiny note on the back that they are facsimiles and to credit the repository

7. other ideas:

a. offprints of journal articles

b. sound bites/podcasts such as "The Sounds of History"

H. Education

1. two functions of education through archival outreach:

a. disseminate basic facts about historical events, for national or local reasons

b. make the public aware of what our institution does

(1) by concentrating on our holdings and showing off what we have

2) spreading a subliminal message of corporate pride, or

(3) blatantly demonstrating the treasures among our holdings or our new acquisitions

I. Public relations and archives

1. two functions of public relations through archival/museum outreach

a. use an exhibit to honor someone wealthy (who has been--or you hope soon will be--beneficent to your institution)

b. use it to encourage contributions from and to the community

2. seven-step planning process to facilitate public programming

a. identify the audience(s) for your programs

b. choose among techniques for assessing the needs and wants of the audience(s)

c. identify product(s) that meet those interests

d. assess your own institutional and personal resources

e. develop objectives for the product(s) and for your institution

f. identify the marketing techniques that fit the audience

g. evaluate the success of the product(s)

~The end~

The time has come to give report

of what you've done and how you sort.

You've learned some skills,

tho' 'tweren't no thrill;

now say your piece here, as you ‘ort.

Click here for the students' review notes for the final half of this course--and give yourself a final exam to show how much you taught yourself.

~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~~

A final request:

No one likes futility. If you appreciate the hundreds of hours of work and thousands of hours of experience that went into compiling this online course in archives and over 100 pages of notes for your edification, please let us know.